Osteoporosis is a progressive metabolic bone disease that decreases bone mineral density (bone mass per unit volume), with deterioration of bone structure. Skeletal weakness leads to fractures with minor or inapparent trauma, particularly in the thoracic and lumbar spine, wrist, and hip (called fragility fractures). Diagnosis is by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA scan) or by confirmation of a fragility fracture. Prevention and treatment involve risk factor modification, calcium and vitamin D supplements, exercises to maximize bone and muscle strength, improve balance, and minimize the risk of falls, and drug therapy to preserve bone mass or stimulate new bone formation.

Bone is continually being formed and resorbed. Normally, bone formation and resorption are closely balanced. Osteoblasts (cells that make the organic matrix of bone and then mineralize bone) and osteoclasts (cells that resorb bone) are regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitonin, estrogen, vitamin D, various cytokines, and other local factors such as prostaglandins.

Peak bone mass in men and women occurs around age 30. Men have higher bone mass than women. After achieving peak, bone mass plateaus for about 10 years, during which time bone formation approximately equals bone resorption. After this, bone loss occurs at a rate of about 0.3 to 0.5%/year. Beginning with menopause, bone loss accelerates in women to about 3 to 5%/year for about 5 to 7 years and then the rate of loss decelerates. While historically recognized as present, differences suggesting that Blacks achieve higher peak bone mass are being reassessed to better delineate the accuracy and relevance of these differences, as well as whether race should be considered when interpreting test values.

Osteoporotic bone loss affects cortical and trabecular (cancellous) bone. Cortical thickness and the number and size of trabeculae decrease, resulting in increased porosity. Trabeculae may be disrupted or entirely absent. Trabecular bone loss occurs more rapidly than cortical bone loss because trabecular bone is more porous and bone turnover is higher. However, loss of both types contributes to skeletal fragility.

A fragility fracture occurs after less trauma than might be expected to fracture a normal bone. Falls from a standing height or less, including falls out of bed, are typically considered fragility fractures. The most common sites for fragility fractures are the following:

Other sites may include the proximal humerus and pelvis.

Fractures at sites such as the nose, ribs, clavicle, and metatarsals are not considered osteoporosis-related fractures.

Osteoporosis can develop as a primary disorder or secondarily due to some other factor. The sites of fracture are similar in primary and secondary osteoporosis.

More than 95% of osteoporosis in women and about 80% in men is primary and therefore without an identifiable underlying cause. Most cases occur in postmenopausal women and older men. However, certain conditions may accelerate bone loss in patients with primary osteoporosis. Gonadal insufficiency is an important factor in both men and women; other factors include decreased calcium intake, low vitamin D levels, certain drugs, and hyperparathyroidism. Some patients have an inadequate intake of calcium during the bone growth years of adolescence and thus never achieve peak bone mass.

The major mechanism of bone loss is increased bone resorption, resulting in decreased bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration, but sometimes bone formation is impaired. The mechanisms of bone loss may involve the following:

Fragility fractures rarely occur in children, adolescents, premenopausal women, or men < 50 years with normal gonadal function and no detectable secondary cause, even in those with low bone mass (low Z-scores on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DXA] scans). Such uncommon cases are considered idiopathic osteoporosis.

Secondary osteoporosis accounts for < 5% of osteoporosis in women and about 20% in men. The causes (see table Causes of Secondary Osteoporosis) may also further accelerate bone loss and increase fracture risk in patients with primary osteoporosis.

Patients with chronic kidney disease may have several reasons for low bone mass, including secondary hyperparathyroidism, elevated serum phosphorus, calcitriol deficiency, abnormalities of serum calcium and vitamin D, osteomalacia, and low-turnover bone disorders (adynamic bone disease).TABLECauses of Secondary Osteoporosis

Because stress, including weight bearing, is necessary for bone growth, immobilization or extended sedentary periods result in bone loss. A low body mass index predisposes to decreased bone mass. Certain populations, including white and Asian people, are thought to have a high risk of osteoporosis. However, given the diversity within larger population groups and controversies about whether and how to group people into populations, these differences are being reevaluated. Insufficient dietary intake of calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and vitamin D predisposes to bone loss, as does endogenous acidosis. Tobacco and alcohol use also adversely affect bone mass. A family history of osteoporosis, particularly a parental history of hip fracture, also increases risk. Patients who have had one fragility fracture are at increased risk of having other clinical (symptomatic) fractures and clinically asymptomatic vertebral compression fractures.

Patients with osteoporosis are asymptomatic unless a fracture has occurred. Nonvertebral fractures are typically symptomatic, but about two thirds of vertebral compression fractures are asymptomatic (although patients may have underlying chronic back pain due to other causes such as osteoarthritis). A vertebral compression fracture that is symptomatic begins with acute onset of pain that usually does not radiate, is aggravated by weight bearing, may be accompanied by point spinal tenderness, and typically begins to subside in 1 week. Residual pain may last for months or be constant, in which case additional fractures or underlying spine disorders should be suspected.

Multiple thoracic compression fractures eventually cause dorsal kyphosis, with exaggerated cervical lordosis (dowager’s hump). Abnormal stress on the spinal muscles and ligaments may cause chronic, dull, aching pain, particularly in the lower back. Patients may have shortness of breath due to the reduced intrathoracic volume and/or early satiety due to the compression of the abdominal cavity as the rib cage approaches the pelvis.

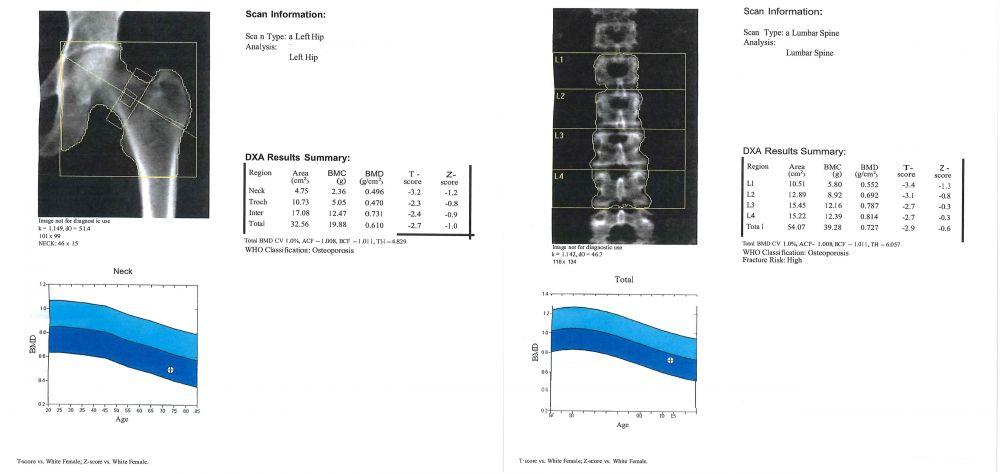

Bone mineral density should be measured using DXA scan to screen people at risk, to provide a quantitative measure of bone loss, and to monitor those undergoing treatment (1).DXA Scan

IMAGE COURTESY OF MARCY B. BOLSTER, MD.

A DXA scan is recommended for the following patients:

Although low bone mineral density (and the associated increased risk of fracture) can be suggested by plain x-rays, it should be confirmed by a bone mineral density measurement. Low bone mineral density can also be suggested by a screening heel or finger DXA scan (eg, done at health fairs). An abnormal screening heel or finger DXA scan warrants a conventional DXA scan to confirm the diagnosis.

DXA is used to measure bone mineral density (g/cm2); it defines osteopenia or osteoporosis (in the absence of osteomalacia), predicts the risk of fracture, and can be used to follow treatment response. Bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, hip, distal radius, or the entire body can be measured. (Quantitative CT scanning can produce similar measurements of the spine or hip but is currently not widely available.) Bone mineral density is ideally measured at two sites, including the lumbar spine and one hip; however, at some centers, measurements are taken of the spine and both hips.

If the spine or a hip is not available for scanning (eg, because of hardware from prior total hip arthroplasty), the distal radius can be scanned (called “1/3 radius” on the DXA scan report). The distal radius should also be scanned in a patient with hyperparathyroidism because this is the most common site of bone loss in hyperparathyroidism.

DXA results are reported as T-scores and Z-scores. The T-score corresponds to the number of standard deviations that the patient’s bone mineral density differs from the peak bone mass of a healthy, young person of the same sex and race/ethnicity. The World Health Organization establishes cutoff values for T-scores that define osteopenia and osteoporosis. A T-score < -1.0 and > -2.5 defines osteopenia. A T-score ≤ -2.5 defines osteoporosis.

The Z-score corresponds to the number of standard deviations that the patient’s bone mineral density differs from that of a person of the same age and sex and should be used for children, premenopausal women, or men < 50 years. If the Z-score is ≤ -2.0, bone mineral density is low for the patient’s age and secondary causes of bone loss should be considered.

Current central DXA systems can also assess vertebral deformities in the lower thoracic and lumbar spine, a procedure termed vertebral fracture assessment (VFA). Vertebral deformities, in the absence of trauma, even those clinically silent, are diagnostic of osteoporosis and are predictive of an increased risk of future fractures. VFA is more likely to be useful in patients with height loss ≥ 3 cm. If the VFA results reveal suspected abnormalities, plain x-rays should be done to confirm the diagnosis.

The need for drug therapy is based on the probability of fracture, which depends on DXA results as well as other factors. The fracture risk assessment (FRAX) score (see Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) predicts the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic (hip, spine, forearm, or humerus) fracture in untreated patients. The score accounts for several significant risk factors for bone loss and fracture. If the FRAX score is above certain thresholds (in the US, a ≥ 20% probability of major osteoporotic fracture or 3% probability of hip fracture), drug therapy should generally be recommended. There are limitations to the use of the FRAX score because it does not account for several factors, including history of falls, the patient’s bone mineral density at the lumbar spine, or family history of vertebral fractures.

Monitoring for ongoing bone loss or the response to treatment with serial DXA scans should be done using the same DXA machine, and the comparison should use actual bone mineral density (g/cm2) rather than T-score. In patients with osteopenia, DXA should be repeated periodically to determine whether there is ongoing bone loss or development of frank osteoporosis requiring treatment. The frequency for follow-up DXA scanning varies from patient to patient, but some reasonable guidelines are as follows:

Results may help identify patients at higher risk of fractures due to a suboptimal response to osteoporosis treatment (1). Patients who have a significantly lower bone mineral density should be evaluated for secondary causes of bone loss, poor drug absorption (if taking an oral bisphosphonate), and (except patients treated with IV bisphosphonates) drug adherence.

Bones show decreased radiodensity and loss of trabecular structure, but not until about 30% of bone has been lost. However, plain x-rays are important for documenting fractures resulting from bone loss. Loss of vertebral body height and increased biconcavity characterize vertebral compression fractures. Thoracic vertebral fractures may cause anterior wedging of the bone. Vertebral fractures at T4 or above raise concern of cancer rather than primary osteoporosis. Plain x-rays of the spine should be considered in older patients with severe back pain and localized vertebral spinous tenderness. In long bones, although the cortices may be thin, the periosteal surface remains smooth.Osteoporotic Compression Fracture

PHOTO COURTESY OF MARCY B. BOLSTER, MD.

Corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis is most likely to cause vertebral compression fractures but may also cause fractures at other sites where osteoporotic fractures are common. Hyperparathyroidism can be differentiated when it causes subperiosteal resorption or cystic bone lesions (rarely). Osteomalacia may cause abnormalities on imaging tests similar to those of osteoporosis.Osteopenia: Differentiating Osteoporosis and Osteomalacia

| Osteopenia is decreased bone mass. Two metabolic bone diseases decrease bone mass: osteoporosis and osteomalacia.In osteoporosis, bone mass decreases, but the ratio of bone mineral to bone matrix is normal.In osteomalacia, the ratio of bone mineral to bone matrix is low.Osteoporosis results from a combination of low peak bone mass, increased bone resorption, and impaired bone formation. Osteomalacia is due to impaired mineralization, usually because of severe vitamin D deficiency or abnormal vitamin D metabolism (see Vitamin D). Osteomalacia can be caused by disorders that interfere with vitamin D absorption (eg, celiac disease) and by certain drugs (eg, antiseizure drugs). Osteoporosis is much more common than osteomalacia in the US. The two disorders may coexist, and their clinical expression is similar; moreover, patients with osteoporosis may have mild to moderate vitamin D deficiency.Osteomalacia should be suspected if the patient has bone pain, recurrent rib or other unusual fractures, and the vitamin D level is consistently very low. To definitively differentiate between the two disorders, clinicians can do a tetracycline-labeled bone biopsy, but this is rarely warranted. |

An evaluation for secondary causes of bone loss should be considered in a patient with a Z-score ≤ -2.0 with unexplained fractures. Laboratory testing should usually include the following:

Other tests such as thyroid-stimulating hormone or free thyroxine to check for hyperthyroidism, measurements of urinary free cortisol, and blood counts and other tests to rule out cancer, especially myeloma (eg, serum free light chains and urine protein electrophoresis), should be considered depending on the clinical presentation.

Patients with weight loss should be screened for gastrointestinal disorders (eg, malabsorption, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease) as well as cancer. Bone biopsy is reserved for unusual cases (eg, young patients with fragility fractures and no apparent cause, patients with chronic kidney disease who may have other bone disorders, patients with persistently very low vitamin D levels suspected of having osteomalacia).

Levels of fasting serum C-telopeptide cross-links (CTX) or urine N-telopeptide cross-links (NTX) reflect increased bone resorption. Although reliability varies for routine clinical use, elevated levels of CTX and NTX may be helpful in predicting fracture risk in an untreated patient, monitoring response to therapy, or with the timing of a drug holiday (2). In patients on drug therapy, levels should be markedly suppressed. If not, abnormal absorption or poor adherence to treatment regimen should be suspected.

The goals of treatment of osteoporosis are to preserve bone mass, prevent fractures, decrease pain, and maintain function.

The rate of bone loss can be slowed with drugs, but adequate calcium and vitamin D ingestion and physical activity are critical to maintaining optimal bone mineral density. Modifiable risk factors should also be addressed.

Risk factor modification can include increasing weight-bearing exercise, minimizing caffeine and alcohol intake, and smoking cessation. The optimal amount of weight-bearing exercise is not established, but an average of 30 minutes/day is recommended. A physical therapist can develop a safe exercise program and demonstrate how to safely perform daily activities to minimize the risk of falls and spine fractures.

All men and women should consume at least 1000 mg of elemental calcium daily. An intake of 1200 mg/day (including dietary consumption) is recommended for postmenopausal women and older men and for periods of increased requirements, such as pubertal growth, pregnancy, and lactation. Calcium intake should ideally be from dietary sources, with supplements used if dietary intake is insufficient. Calcium supplements are taken most commonly as calcium carbonate or calcium citrate. Calcium citrate is better absorbed in patients with achlorhydria, but both are well absorbed when taken with meals. Patients taking gastric acid suppressants (eg, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers) or those who have had gastric bypass surgery should take calcium citrate to maximize absorption. Calcium should be taken in divided doses of 500 to 600 mg 2 or 3 times a day.

Vitamin D supplementation is recommended with 600 to 800 units/day. Patients with vitamin D deficiency may need even higher doses. Supplemental vitamin D is usually given as cholecalciferol, the natural form of vitamin D, although ergocalciferol, the synthetic plant-derived form, is probably also acceptable. The 25-hydroxy vitamin D level should be ≥ 30 ng/mL.

Bisphosphonates are first-line drug therapy. By inhibiting bone resorption, bisphosphonates preserve bone mass and can decrease vertebral and hip fractures by up to 50%. Bone turnover is reduced after 3 months of bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk reduction is evident as early as 1 year after beginning therapy. DXA scans, when done serially to monitor response to treatment, should be done at appropriate intervals (except for romosozumab, 2 years or longer). Bisphosphonates can be given orally or IV. Bisphosphonates include the following:

Evidence supports a treatment duration with oral alendronate for 5 years or with IV zoledronic acid for 3 to 6 years (1). Optimal durations for other bisphosphonates are not yet known.

Oral bisphosphonates must be taken on an empty stomach with a full (8-oz, 250 mL) glass of water, and the patient must remain upright for at least 30 minutes (60 minutes for ibandronate) and not take anything else by mouth during this time period. These drugs are safe to use in patients with a creatinine clearance > 35 mL/minute. Oral bisphosphonates can cause esophageal irritation. Esophageal disorders that delay transit time and symptoms of upper gastrointestinal disorders are relative contraindications to oral bisphosphonates. IV bisphosphonates are indicated if a patient is unable to tolerate or is nonadherent with oral bisphosphonates.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures have been rarely reported in patients receiving antiresorptive therapy with bisphosphonates or denosumab. Risk factors include invasive dental procedures, IV bisphosphonate use, and cancer. The benefits of reduction of osteoporosis-related fractures far outweigh this small risk. Although some dentists ask a patient to discontinue a bisphosphonate for several weeks or months before an invasive dental procedure, it is not clear that doing so decreases the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Long-term bisphosphonate use may increase the risk of atypical femoral fractures. These fractures occur in the mid-shaft of the femur with minimal or no trauma and may be preceded by weeks or months of thigh pain. The fractures may be bilateral even if symptoms are only unilateral.

To minimize fracture incidence, consideration should be given to stopping bisphosphonates (a bisphosphonate holiday) after about

Intermittent cessation of bisphosphonate treatment (drug holiday), as well as initiation and duration of therapy, depend on patient risk factors such as age, comorbidities, prior fracture history, DXA scan results, and fall risk. The drug holiday is 1 year or longer. Patients on a bisphosphonate holiday should be closely monitored for a new fracture or accelerated bone loss evident on a DXA scan, especially after being off therapy for 2 years or more.

During therapy with an antiresorptive drug, such as a bisphosphonate, bone turnover is suppressed as evidenced by low fasting N-telopeptide cross-links (< 40 nmol/L) or C-telopeptide cross-links. These markers may remain low for ≥ 2 years off drug therapy. In untreated patients, an increase in levels of bone turnover markers, particularly with higher levels, indicates an increased risk of fracture. However, it is not clear whether levels of bone turnover markers should be used as criteria for when to start or end a drug holiday.

Intranasal salmon calcitonin should not regularly be used for treating osteoporosis. Salmon calcitonin may provide short-term analgesia after an acute fracture, such as a painful vertebral fracture, due to an endorphin effect. It has not been shown to reduce fractures.

Estrogen can preserve bone mineral density and prevent fractures. Most effective if started within 4 to 6 years of menopause, estrogen is given orally and may slow bone loss and possibly reduce fractures even when started much later. Use of estrogen increases the risk of thromboembolism and endometrial cancer and may increase the risk of breast cancer. The risk of endometrial cancer can be reduced in women with an intact uterus by taking a progestin with estrogen (see Hormone therapy). However, taking a combination of a progestin and estrogen increases the risk of breast cancer, coronary artery disease, stroke, and biliary disease. Because of these concerns and the availability of other treatments for osteoporosis, the potential harms of estrogen treatment for osteoporosis treatment outweigh its potential benefits for most women; when treatment is initiated, a short course with close monitoring should be considered.

Raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that may be appropriate for treatment of osteoporosis in women who cannot take bisphosphonates. It is given orally once daily and reduces vertebral fractures by about 50% but has not been shown to reduce hip fractures. Raloxifene does not stimulate the uterus and antagonizes estrogen effects in the breast. It has been shown to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer. Raloxifene has been associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism.

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody against RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand) and reduces bone resorption by osteoclasts. Denosumab may be helpful in patients not tolerant of or unresponsive to other therapies or in patients with impaired renal function. This drug has been found to have a good safety profile at 10 years of therapy. Denosumab is contraindicated in patients with hypocalcemia because it can cause calcium shifts that result in profound hypocalcemia and adverse effects such as tetany. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures have been rarely reported in patients taking denosumab.

Patients taking denosumab should not undergo a drug holiday because stopping this drug may cause a rapid loss in bone mineral density and, importantly, increase the risk of fractures, particularly vertebral fractures, sometimes multiple. If and when denosumab is discontinued, transition to a bisphosphonate such as IV zoledronic acid should be considered for a year or more, depending upon ongoing risk of fracture.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody against sclerostin (a small protein made by osteocytes that inhibits new bone formation by osteoblasts). It has both antiresorptive and anabolic effects and has been shown to increase bone mineral density in the hip and lumbar spine and reduce fracture risk in postmenopausal women (2). Romosozumab is indicated for patients with severe osteoporosis, particularly in older people, those who are frail, and those with an increased risk of falling. It should also be considered in patients who fracture despite adequate antiresorptive therapy. It is given via monthly subcutaneous injection for 1 year (3). Romosozumab treatment for 1 year followed by alendronate for 1 year is more efficacious than treatment with alendronate for 2 years (3). Romosozumab carries a black box warning due to increased risk for cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death. It should not be initiated within 12 months of a patient having had a myocardial infarction or stroke. As with denosumab, when romosozumab is discontinued, bisphosphonate therapy should be given to prevent rapid bone loss.

The immediate initiation of antiresorptive agent therapy after an osteoporotic fracture has been controversial because of a theoretical concern that these agents may impede bone healing. However, recent American Society of Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) treatment recommendations for secondary prevention of fractures include the recommendation to initiate an oral bisphosphonate during the hospitalization for the fracture (4). Also, there is no reason to delay therapy in order to obtain a DXA scan because a hip or vertebral fragility fracture establishes the presence of osteoporosis.

Anabolic agents include teriparatide (synthetic PTH [PTH1-34]) and abaloparatide (a human PTH analog that binds to PTH type 1 receptor). They are given daily by subcutaneous injection and increase bone mass, stimulate new bone formation, and reduce the risk of fractures. Patients taking an anabolic agent should have a creatinine clearance > 35 mL/minute. Romosozumab, the monoclonal antibody against sclerostin, has anabolic as well as antiresorptive effects.

These three anabolic agents (teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab) are generally indicated for patients who have the following characteristics:

Any of these three anabolic agents can be considered for use during a bisphosphonate holiday.

The use of anabolic agents to treat osteoporosis had been limited to 2 years based on a black box warning because of concern of increased risk of developing osteosarcoma in initial 2-year clinical trials, but the restriction of 2 years of therapy is no longer required. Consequently, although 2 years of treatment with an anabolic agent remains a reasonable course of therapy, giving a second 2-year course of therapy can now be considered. However, after completion of a treatment course with an anabolic agent, the bone mineral density gains are quickly lost if a patient is not quickly transitioned to an antiresorptive agent such as a bisphosphonate.

Anabolic agents are safe to initiate at any time after a fracture. It is not clear whether early post-fracture use of anabolic agents accelerates bone healing.

Many older patients are at risk of falls because of poor coordination and balance, poor vision, muscle weakness, confusion, and use of drugs that cause postural hypotension or alter the sensorium. Core-strengthening exercises may increase stability. Educating patients about the risks of falls and fractures, modifying the home environment for safety, and developing individualized programs to increase physical stability and attenuate risk are important for preventing fractures.

Acute back pain resulting from a vertebral compression fracture should be treated with orthopedic support, analgesics, and, when muscle spasm is prominent, moist heat and massage. Core-strengthening exercises are helpful for patients who have back pain and a prior healed vertebral fracture. Chronic backache may be relieved by exercises to strengthen paravertebral muscles. Avoiding heavy lifting can help. Bed rest should be minimized, and consistent, carefully designed weight-bearing exercise should be encouraged.

In some patients, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty can be used to relieve severe pain due to a new vertebral fragility fracture; however, the evidence for efficacy is inconclusive. In vertebroplasty, methyl methacrylate is injected into the vertebral body. In kyphoplasty, the vertebral body is first expanded with a balloon then injected with methyl methacrylate. These procedures may reduce deformity in the injected vertebrae but do not reduce and may even increase the risk of fractures in adjacent vertebrae. Other risks may include rib fractures, cement leakage, pulmonary embolism, or myocardial infarction. Further study to determine indications for these procedures is warranted.

The goals of prevention are 2-fold: preserve bone mass and prevent fractures. Preventive measures are indicated for the following:

Preventive measures for all of these patients include appropriate calcium and vitamin D intake, weight-bearing exercise, fall prevention, and other ways to reduce risk (eg, avoiding tobacco and limiting alcohol). In addition, drug therapy is indicated for patients who have osteoporosis or who have osteopenia if they are at increased risk of fracture, such as those with a high FRAX score, and patients taking glucocorticoids. Drug therapy tends to involve the same drugs as are given for treatment of osteoporosis. Educating patients and the community about the importance of bone health remains of utmost importance.

The following English-language resources may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of these resources.