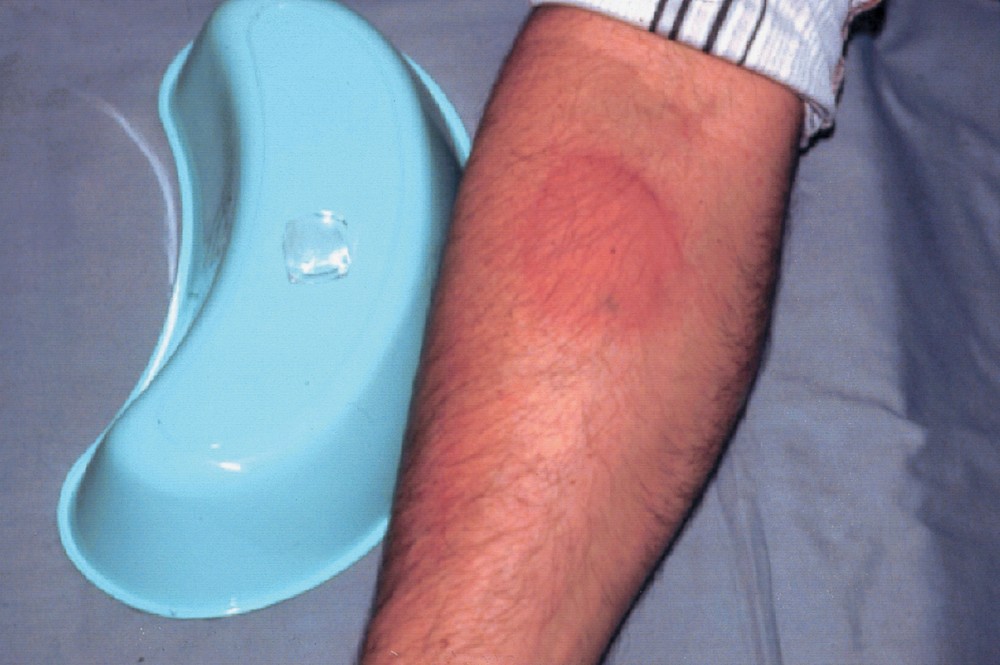

Urticaria consists of migratory, well-circumscribed, erythematous, pruritic plaques on the skin.

Urticaria also may be accompanied by angioedema, which results from mast cell and basophil activation in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissues and manifests as edema of the face and lips, extremities, or genitals. Angioedema can occur in the bowel and present as colicky abdominal pain. Angioedema can be life-threatening if airway obstruction occurs because of laryngeal edema or tongue swelling.

(See also Evaluation of the Dermatologic Patient.)

Urticaria results from the release of histamine, bradykinin, kallikrein, and other vasoactive substances from mast cells and basophils in the superficial dermis, resulting in intradermal edema caused by capillary and venous vasodilation and occasionally caused by leukocyte infiltration.

The process can be immune mediated or nonimmune mediated.

Immune-mediated mast cell activation includes

Nonimmune-mediated mast cell activation includes

Urticaria is classified as acute (< 6 weeks) or chronic (> 6 weeks); acute cases (70%) are more common than chronic (30%).

Acute urticaria (see Table: Some Causes of Urticaria) most often results from

A presumptive trigger (eg, drug, food ingestion, insect bite or sting, infection) occasionally can be identified.

Chronic urticaria most often results from

Chronic urticaria often lasts months to years, eventually resolving without a cause being found.TABLESome Causes of Urticaria

Images of Urticaria

Because there are no definitive diagnostic tests for urticaria, evaluation largely relies on history and physical examination.

History of present illness should include a detailed account of the individual episodes of urticaria, including distribution, size, and appearance of lesions; frequency of occurrence; duration of individual lesions; and any prior episodes. Activities and exposures during, immediately before, and within the past 24 hours of the appearance of urticaria should be noted. Clinicians specifically should ask about recent exercise; exposure to potential allergens (see Table: Some Causes of Urticaria), insects, or animals; new laundry detergent or soaps; new foods; recent infections; or recent stressful life events. The patient should be asked about the duration between any suspected trigger and the appearance of urticaria and which particular triggers are suspected. Important associated symptoms include pruritus, rhinorrhea, swelling of the face and tongue, and dyspnea.

Review of systems should seek symptoms of causative disorders, including fever, fatigue, abdominal pain, and diarrhea (infection); heat or cold intolerance, tremor, or weight change (autoimmune thyroiditis); joint pain (cryoglobulinemia, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]); malar rash (SLE); dry eyes and dry mouth (Sjögren syndrome); cutaneous ulcers and hyperpigmented lesions after resolution of urticaria (urticarial vasculitis); small pigmented papules (mastocytosis); lymphadenopathy (viral illness, cancer, serum sickness); acute or chronic diarrhea (viral or parasitic enterocolitis); and fevers, night sweats, or weight loss (cancer).

Past medical history should include a detailed allergy history, including known atopic conditions (eg, allergies, asthma, eczema) and known possible causes (eg, autoimmune disorders, cancer). All drug use should be reviewed, including over-the-counter drugs and herbal products, specifically any agents particularly associated with urticaria (see Table: Some Causes of Urticaria). Family history should elicit any history of rheumatoid disease, autoimmune disorders, or cancer. Social history should cover any recent travel and any risk factors for transmission of infectious disease (eg, hepatitis, HIV).

Vital signs should note the presence of bradycardia or tachycardia and tachypnea. General examination should immediately seek any signs of respiratory distress and also note cachexia, jaundice, or agitation.

Examination of the head should note any swelling of the face, lips, or tongue; scleral icterus; malar rash; tender and enlarged thyroid; lymphadenopathy; or dry eyes and dry mouth. The oropharynx should be inspected and the sinuses should be palpated and transilluminated for signs of occult infection (eg, sinus infection, tooth abscess).

Abdominal examination should note any masses, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or tenderness. Neurologic examination should note any tremor or hyperreflexia or hyporeflexia. Musculoskeletal examination should note the presence of any inflamed or deformed joints.

Skin examination should note the presence and distribution of urticarial lesions as well as any cutaneous ulceration, hyperpigmentation, small papules, or jaundice. Urticarial lesions usually appear as well-demarcated transient swellings involving the dermis. These swellings are typically red and vary in size from pinprick to covering wide areas. Some lesions can be very large. In other cases, smaller urticarial lesions may become confluent. However, skin lesions also may be absent at the time of the visit. Maneuvers to evoke physical urticaria can be done during the examination, including exposure to vibration (tuning fork), warmth (tuning fork held under warm water), cold (stethoscope or chilled tuning fork), water, or pressure (lightly scratching an unaffected area with a fingernail).

The following findings are of particular concern:

Acute urticaria is nearly always due to some defined exposure to a drug or physical stimulus or an acute infectious illness. However, the trigger is not always clear from the history, particularly because allergy may develop without warning to a previously tolerated substance.

Most chronic urticaria is idiopathic. The next most common cause is an autoimmune disorder. The causative autoimmune disease is sometimes clinically apparent. Urticarial vasculitis sometimes is associated with connective tissue disorders (particularly SLE or Sjögren syndrome). In urticarial vasculitis, urticaria is accompanied by findings of cutaneous vasculitis; it should be considered when the urticaria is painful rather than pruritic, lasts > 48 hours, does not blanch, or is accompanied by vesicles or purpura.

Usually, no testing is needed for an isolated episode of urticaria unless symptoms and signs suggest a specific disorder (eg, infection).

Unusual, recurrent, or persistent cases warrant further evaluation. Referral for allergy skin testing should be done, and routine laboratory tests should consist of complete blood count, blood chemistries, liver tests, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Further testing should be guided by symptoms and signs (eg, of autoimmune disorders) and any abnormalities on the screening tests (eg, hepatitis serologies and ultrasonography for abnormal liver tests; ova and parasites for eosinophilia; cryoglobulin titer for elevated liver tests or elevated creatinine; thyroid autoantibodies for abnormal TSH).

Skin biopsy should be done if there is any uncertainty as to the diagnosis or if wheals persist > 48 hours (to rule out urticarial vasculitis).

Clinicians should be cautious when recommending the patient do an empiric challenge (eg, “Try such and such again and see whether you get a reaction”) because subsequent reactions may be more severe.

Any identified causes are treated or remedied. Implicated drugs or foods should be stopped.

Nonspecific symptomatic treatment (eg, taking cool baths, avoiding hot water and scratching, wearing loose clothing) may be helpful.

Antihistamines remain the mainstay of treatment. They must be taken on a regular basis, rather than as needed. Newer oral antihistamines often are preferred because of once-daily dosing and because some are less sedating. Appropriate choices include

Older oral antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine 10 to 25 mg every 4 to 6 hours; diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours) are sedating but inexpensive and sometimes quite effective.

Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 30 to 40 mg orally once/day) are given for severe symptoms but should not be used long term. Topical corticosteroids or topical antihistamines are not beneficial.

Patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria often do not respond to antihistamines or other drugs commonly used. Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody that can suppress certain allergic reactions, may help relieve symptoms, but experience with this use is limited.

Patients who have angioedema involving the oropharynx or any involvement of the airway should receive epinephrine 0.3 mL of 1:1000 solution sc and be admitted to the hospital. On discharge, patients should be supplied with and trained in the use of an auto-injectable epinephrine pen.

The older oral antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine) are sedating and can cause confusion, urinary retention, and delirium. They should be used cautiously to treat urticaria in older patients.