Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disorder resulting in noncaseating granulomas in one or more organs and tissues; etiology is unknown. The lungs and lymphatic system are most often affected, but sarcoidosis may affect any organ. Pulmonary symptoms range from none to cough, exertional dyspnea and, rarely, lung or other organ failure. Diagnosis usually is first suspected because of pulmonary involvement and is confirmed by chest x-ray, biopsy, and exclusion of other causes of granulomatous inflammation. First-line treatment is corticosteroids. Prognosis is excellent for limited disease but poor for more advanced disease.

Sarcoidosis most commonly affects people aged 20 to 40 but occasionally affects children and older adults. Worldwide, prevalence is greatest in black Americans and ethnic northern Europeans, especially Scandinavians. Disease presentation varies widely by racial and ethnic background, with black Americans having more frequent extrathoracic manifestations. Sarcoidosis is more prevalent in women.

Löfgren syndrome manifests as a triad of acute polyarthritis, erythema nodosum, and hilar adenopathy. Fever, malaise, and uveitis, and parotitis may also be present. Löfgren syndrome is more common among people of European ancestry. Löfgren syndrome is self-limited. Patients can usually be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone. Rate of relapse is low.

Heerfordt syndrome (uveoparotid fever) manifests as swelling of the parotid gland (due to sarcoid infiltration), uveitis, chronic fever, and less often palsy of the facial nerve. Heerfordt syndrome can be self-limited. Treatment is the same as for sarcoidosis.

Blau syndrome is a sarcoidosis-like disease inherited in a autosomal dominant fashion that manifests in children. It is not known whether Blau syndrome arises through the same mechanism as sarcoidosis diagnosed in adults. In Blau syndrome, children present before the age of 4 years with arthritis, rash, and uveitis. Blau syndrome is often self-limited. Symptoms usually are relieved with NSAIDs.

Sarcoidosis is thought to be due to an inflammatory response to an environmental antigen in a genetically susceptible person. Proposed triggers include

Tobacco use is inversely correlated with sarcoidosis.

Evidence supporting genetic susceptibility includes the following:

The unknown antigen triggers a cell-mediated immune response that is characterized by the accumulation of T cells and macrophages, release of cytokines and chemokines, and organization of responding cells into granulomas. Clusters of disease in families and communities suggest a genetic predisposition, shared exposures, or, less likely, person-to-person transmission.

The inflammatory process leads to formation of noncaseating granulomas, the pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis. Granulomas are collections of mononuclear cells and macrophages that differentiate into epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells and are surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, fibroblasts, and collagen. Granulomas occur most commonly in the lungs and lymph nodes but can involve any organ and cause significant dysfunction. Granulomas in the lungs are distributed along lymphatics, with most occurring in peribronchiolar, subpleural, and perilobular regions. Granuloma accumulation distorts architecture in affected organs. Whether granulomas lead directly to fibrosis or run a parallel course is not known.

Hypercalcemia may occur because of increased conversion of vitamin D to the activated form (1,25 hydroxy vitamin D) by macrophages. Hypercalciuria may be present, even in patients with normal serum calcium levels. Nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis may occur, sometimes leading to chronic kidney disease.

Symptoms and signs depend on the site and degree of involvement and vary over time, ranging from spontaneous remission to chronic indolent illness. Accordingly, frequent reassessment for new symptoms in different organs is needed. Most cases are probably asymptomatic and thus go undetected. Pulmonary disease occurs in > 90% of adult patients.

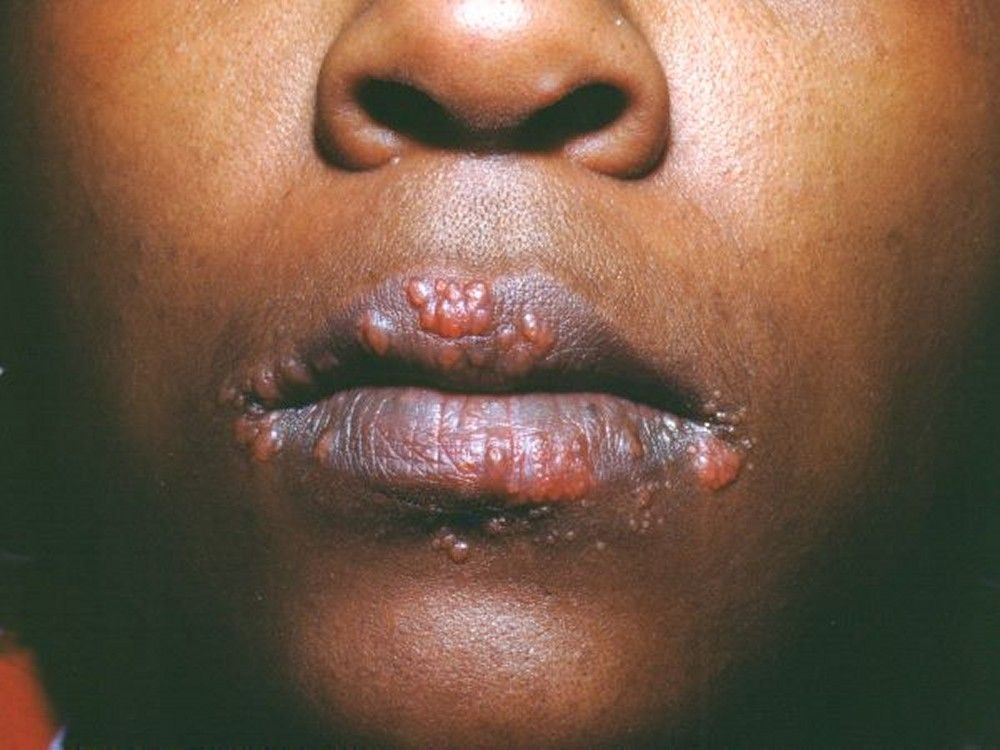

Symptoms and signs may include dyspnea, cough, chest discomfort, and crackles. Fatigue, malaise, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, and low-grade fever are also common. Sarcoidosis can manifest as fever of unknown origin. Systemic involvement causes various symptoms (see table Systemic Involvement in Sarcoidosis), which vary by race, sex, and age. Blacks are more likely than whites to have involvement of the eyes, liver, bone marrow, peripheral lymph nodes, and skin; erythema nodosum is an exception. Women are more likely to have erythema nodosum and eye or nervous system involvement. Men and older patients are more likely to be hypercalcemic.Manifestations of Sarcoidosis

Children with sarcoidosis may present with Blau syndrome (arthritis, rash, uveitis), or manifestations similar to those of adults. Sarcoidosis may be confused with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) in this age group.TABLESystemic Involvement in Sarcoidosis

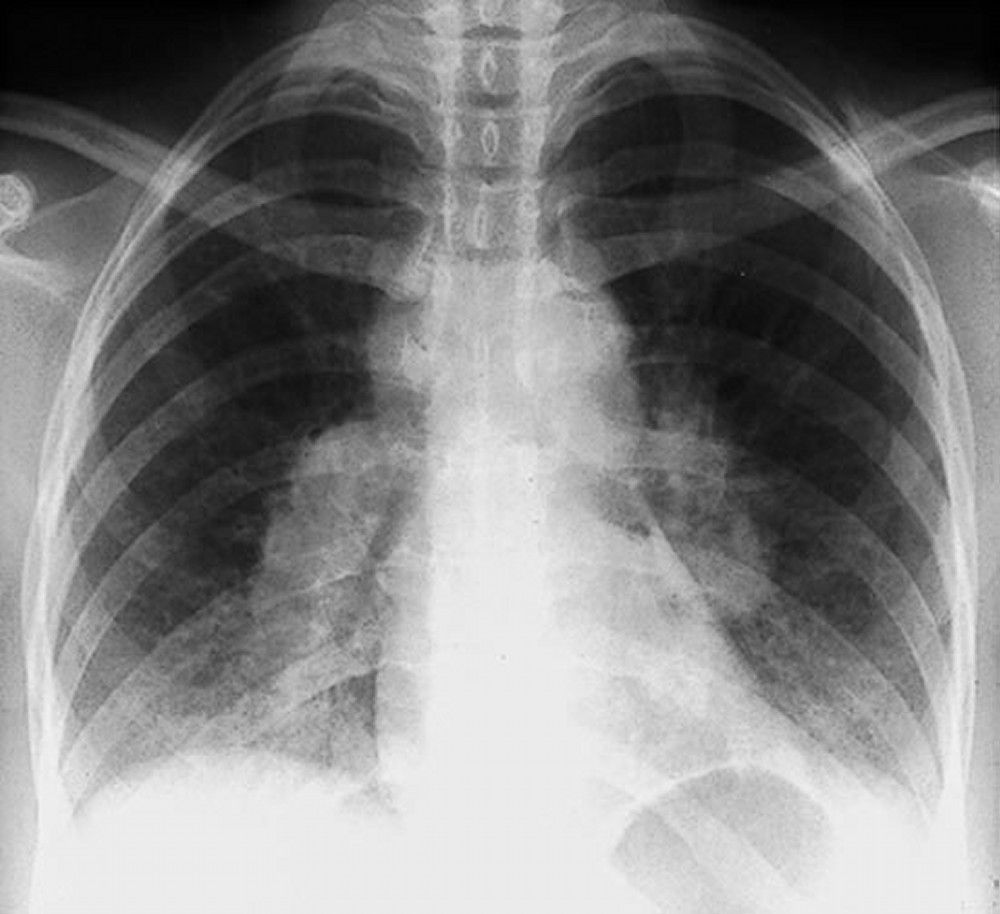

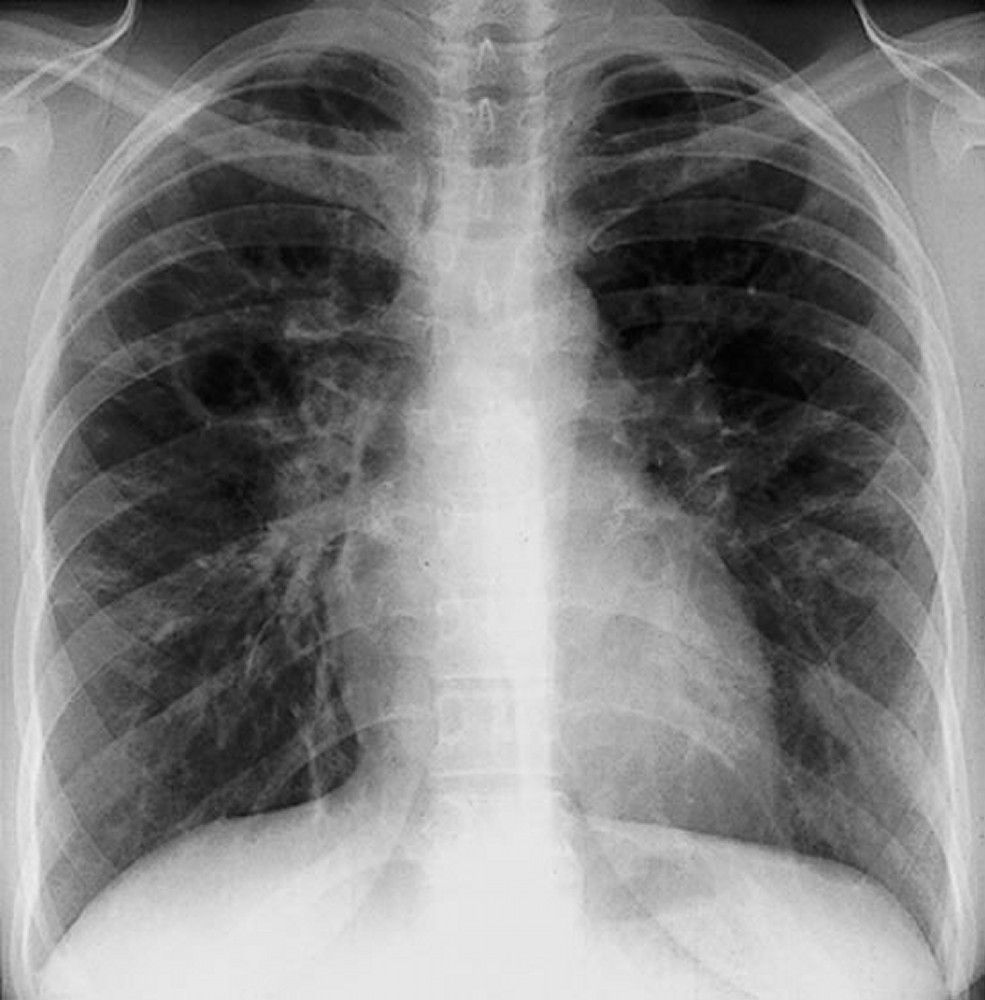

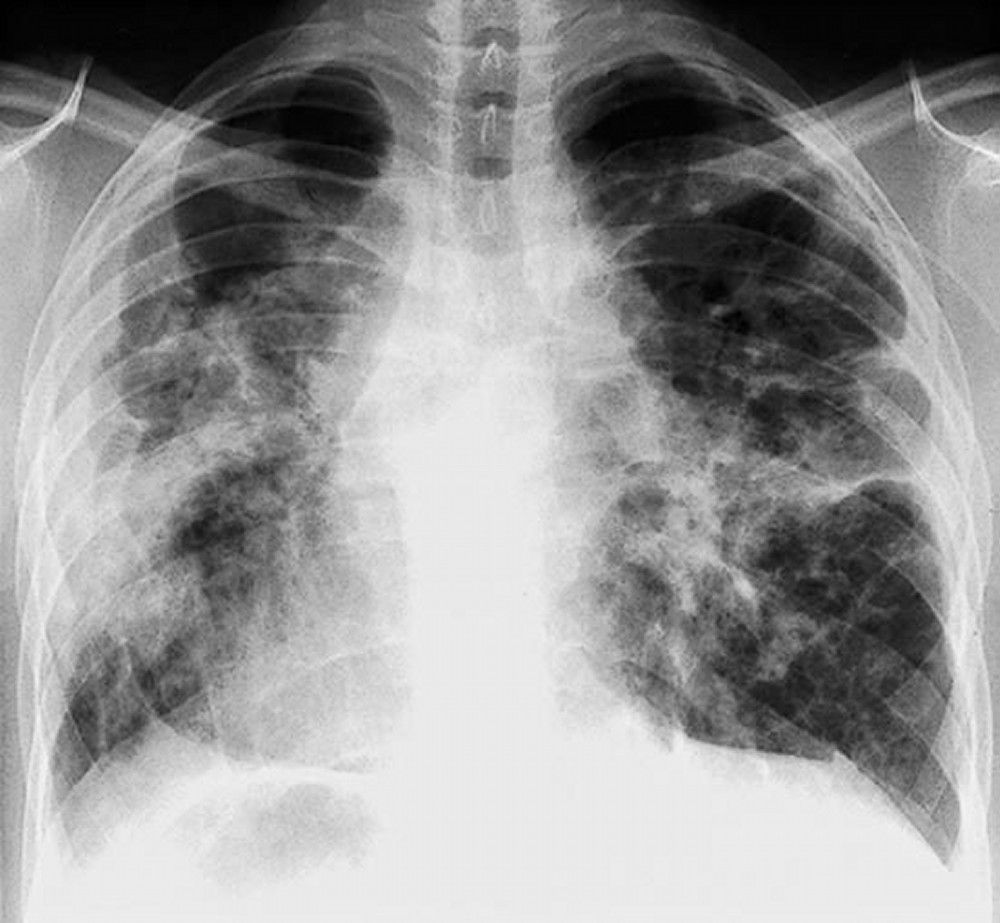

Sarcoidosis is most often suspected when hilar adenopathy is incidentally detected on chest x-ray. Bilateral hilar adenopathy is the most common abnormality. If sarcoidosis is suspected, a chest x-ray should be the first test if it has not already been done. The x-ray appearance tends to roughly predict the likelihood of spontaneous remission (see table Chest X-ray Staging of Sarcoidosis) in patients with only thoracic lymph node involvement. However, staging sarcoidosis by chest x-ray can be misleading; for example, extrapulmonary sarcoidosis, such as cardiac or neurologic sarcoidosis, can portend a poor prognosis in the absence of evidence of pulmonary involvement. Also, chest x-rays findings predict pulmonary function poorly, so that chest x-ray appearance may not accurately indicate the severity of pulmonary sarcoidosis.TABLEChest X-ray Staging of Sarcoidosis

A normal chest x-ray (stage 0) does not exclude the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, particularly when cardiac or neurologic involvement is suspected. A high-resolution CT is more sensitive for detecting hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and parenchymal abnormalities. CT findings in more advanced stages (II to IV) include

Imaging in Sarcoidosis

When imaging suggests sarcoidosis, the diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of noncaseating granulomas on biopsy and exclusion of alternative causes of granulomatous disease (see table Differential Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis). Löfgren syndrome does not require confirmation by biopsy.

The diagnostic evaluation, therefore, requires the following:

TABLEDifferential Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis

Appropriate biopsy sites may be obvious from physical examination and initial assessment; peripheral lymph nodes, skin lesions, and conjunctivae are all easily accessible. Endobronchial ultrasound–guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) of a mediastinal or hilar lymph node has a reported diagnostic yield of about 90% and is the diagnostic procedure of choice in patients with intrathoracic involvement.

Bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsy can be used when EBUS-TBNA is nondiagnostic; if the bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsy is nondiagnostic, it can be tried a second time.

If EBUS-TBNA and bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsies are nondiagnostic or if bronchoscopy cannot be tolerated, mediastinoscopy can be done to biopsy mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes, or video-assisted thoracoscopic (VAT) lung biopsy or open-lung biopsy can be done to obtain lung tissue. If sarcoidosis is strongly suspected but a biopsy site is not evident based on examination or imaging findings, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can help identify active sites such as heart, bone, muscle, and brain.

Exclusion of other diagnoses is critical, especially when symptoms and x-ray signs are minimal, because many other disorders and processes can cause granulomatous inflammation (see table Differential Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis). Biopsy tissue should be cultured for fungi and mycobacteria. Exposure history to occupational (silicates, beryllium), environmental (moldy hay, birds, and other antigenic triggers of hypersensitivity pneumonitis), and infectious (tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis) antigens should be explored. Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin testing or interferon gamma release assay should be done early in the assessment.

Severity is assessed according to organ involvement so, for example, with only pulmonary involvement

Pulmonary function test results are often normal in early stages but demonstrate restriction and reduced diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) in advanced disease. Airflow obstruction also occurs and may suggest involvement of the bronchial mucosae. Adding a 6-minute walk test may characterize functional impairment more comprehensively than the results of pulmonary function tests alone. Patients with extensive lung involvement may have normal oxygen saturation at rest but may show desaturation with exertion.

Recommended routine screening tests for extrapulmonary disease include

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium contrast may be appropriate in patients with cardiac symptoms. In patients with neurologic symptoms, brain or spine MRI with or without gadolinium may be needed, and bone scans and electromyography may be appropriate in patients with rheumatologic symptoms. PET scanning appears to be the most sensitive test for detecting bone and other extrapulmonary sarcoidosis and is used together with MRI in patients with cardiac involvement. Abdominal CT with radiopaque contrast agents is not routinely recommended but can provide evidence of hepatic or splenic involvement (eg, enlargement, hypolucent lesions).

Laboratory testing plays an adjunctive role in establishing the diagnosis and determining the extent of organ involvement. Complete blood count with differential may show anemia, eosinophilia, or leukopenia. Serum calcium should be measured to detect hypercalcemia. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and liver test results may be elevated in renal and hepatic sarcoidosis. Total protein may be elevated because of hypergammaglobulinemia. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate is common but nonspecific. Measurement of calcium in a urine specimen collected over 24 hours is recommended to exclude hypercalciuria, even in patients with normal serum calcium levels. Elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels also suggest sarcoidosis but are nonspecific and may be elevated in patients with other conditions (eg, hyperthyroidism, Gaucher disease, silicosis, mycobacterial disease, fungal infections, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, lymphoma). However, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, if elevated, may be useful for monitoring adherence with corticosteroid treatment. ACE levels plummet even when patients are taking low-dose corticosteroids.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is used to help exclude other forms of interstitial lung disease if the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is in doubt and to rule out infections. The findings on BAL vary considerably, but lymphocytosis (lymphocytes > 10%), a CD4+/CD8+ ratio of > 3.5 in the lavage fluid cell differential, or both suggest the diagnosis in the proper clinical context. However, absence of these findings does not exclude sarcoidosis.

Whole-body gallium scanning has been largely replaced by PET scanning. If gallium scanning is available, it may provide useful supportive evidence in the absence of tissue confirmation. Symmetric increased uptake in mediastinal and hilar nodes (lambda sign) and in lacrimal, parotid, and salivary glands (panda sign) are patterns highly suggestive of sarcoidosis. A negative result in patients taking prednisone is unreliable.

Although spontaneous remission is common, disease manifestations and severity are highly variable, and many patients require corticosteroids to relieve symptoms or progressive organ function decline at some time during the disease course. Thus, serial monitoring for evidence of relapse is imperative. Almost two third of patients with sarcoidosis eventually achieve remission with few or no sequelae. In about 50% of patients who have spontaneous remission, remission occurs within the first 3 years after diagnosis. Fewer than 10% of these patients relapse after 2 years. Patients who do not experience remission within 2 to 3 years are likely to have chronic disease.

Sarcoidosis is thought to be chronic in up to 30% of patients, and 10 to 20% experience permanent sequelae. The disease is fatal in 1 to 5% of patients, typically due to respiratory failure caused by pulmonary fibrosis, and less often due to pulmonary hemorrhage caused by aspergilloma. However, in Japan, infiltrative cardiomyopathy causing arrhythmias and heart failure is the most common cause of death.

Prognosis is worse for patients with extrapulmonary sarcoidosis and for blacks. Remission occurs in 89% of whites and 76% of blacks with no extrathoracic disease and in 70% of whites and 46% of blacks with extrathoracic disease.

Good prognostic signs include

Poor prognostic signs include

Little difference is demonstrable in long-term outcome between treated and untreated patients, and relapse is common when treatment ends.

Because sarcoidosis often spontaneously resolves, asymptomatic patients and patients with mild symptoms do not require treatment, although they should be monitored for signs of deterioration. These patients can be followed with serial chest x-rays, pulmonary function tests (including diffusing capacity), and markers of extrathoracic involvement (eg, routine renal and liver function testing, annual slit-lamp ophthalmologic examination). The frequency of follow-up testing is determined by the severity of disease.

Patients who require treatment regardless of stage include those with the following:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are used to treat musculoskeletal discomfort.

Symptom management begins with corticosteroids. The presence of chest imagining abnormalities without significant symptoms or evidence of decline in organ function is not an indication for treatment. A standard protocol is prednisone 20 mg to 40 mg by mouth once a day, depending on symptoms and severity of findings. Alternate-day regimens may be used: eg, prednisone 40 mg by mouth once every other day. Although patients rarely require > 40 mg/day, higher doses may be needed to reduce complications in neurologic disease. Response usually occurs within 6 to 12 weeks, so symptoms and pulmonary function test results may be reassessed between 6 and 12 weeks. Chronic, insidious cases may respond more slowly. Corticosteroids are tapered to a maintenance dose (eg, prednisone 10 to 15 mg/day) after evidence of response and are continued for an additional 6 to 9 months if improvement occurs.

The optimal duration of treatment is unknown. Premature taper can result in relapse. The drug is slowly stopped if response is absent or equivocal. Corticosteroids can ultimately be stopped in most patients, but because relapse occurs up to 50% of the time, monitoring should be repeated, usually every 3 to 6 months. Corticosteroid treatment should be resumed for recurrence of symptoms and signs. Because angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) production is suppressed with low doses of corticosteroids, serial serum ACE levels may be useful in assessing adherence with corticosteroid treatment in patients who have elevated ACE levels.

Inhaled corticosteroids can relieve cough in patients with endobronchial involvement or with hyperreactive airways.

Topical corticosteroids may be useful in dermatologic, nasal sinus, and ocular disease.

Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia should be considered while patients are taking > 20 mg prednisone daily or its equivalent for more than a month and for those who are taking immunosuppressants.

Alendronate or another bisphosphonate may be the treatment of choice for prevention of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Using supplemental calcium or vitamin D risks hypercalcemia due to endogenous production of active vitamin D (1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D) by sarcoidal granulomas. Serum and 24-hour urinary calcium measurements should be normal before starting such supplements.

| The presence of chest imagining abnormalities without significant symptoms or evidence of decline in organ function is not an indication for treatment with corticosteroids. |

Immunosuppressants are often effective in refractory cases. For example, immunosuppressive drugs have been used when:

Prior to adding other immunosuppressants, possible reasons for lack of clinical improvement, such as noncompliance, comorbid disease, pulmonary hypertension, and end-stage fibrosis should be considered.

Methotrexate is the most commonly used immunosuppressant. Patients should be given a 6-month trial of methotrexate 10 to 15 mg/week. Patients should be tested for infection with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus before methotrexate is started. Initially, methotrexate and corticosteroids are both given; over 6 to 8 weeks, the corticosteroid dose can be tapered and, in many cases, stopped. The maximal response to methotrexate, however, may take 6 to 12 months. In such cases, prednisone must be tapered more slowly. Serial blood counts and liver enzyme tests should be done every 1 to 2 weeks initially and then every 4 to 6 weeks once a stable dose is achieved. Folate (1 mg by mouth once a day) is recommended for patients treated with methotrexate.

Other immunosuppressants include azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg by mouth once a day or 200 mg by mouth twice a day can be effective for treating hypercalcemia, arthralgia, skin sarcoidosis, or enlarged uncomfortable or disfiguring peripheral lymph nodes. Ophthalmologic evaluation should be done before hydroxychloroquine is started and every 6 to 12 months during treatment to monitor for its ocular toxicity.

Relapse is common after stopping an immunosuppressant.

Infliximab can be effective for treatment of chronic corticosteroid-dependent pulmonary sarcoidosis, refractory lupus pernio, and neurosarcoidosis. Patients should have a purified protein derivative (PPD) or interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis before beginning therapy. Infliximab is given intravenously 3 to 5 mg/kg once, again 2 weeks later, then once per month. It may take 3 to 6 months for maximal response. Adalimumab can be considered for patients who have been treated successfully with infliximab but have developed antibodies or infusion reactions.

Patients who have heart block or ventricular arrhythmias due to cardiac involvement should have an implantable cardiac defibrillator and pacemaker placed as well as drug therapy.

No available drugs have consistently prevented pulmonary fibrosis.

Treatment of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension is supportive with diuresis and supplemental oxygen. So far therapy with pulmonary vasodilators has not been found to be beneficial (1).

Organ transplantation is an option for patients with end-stage pulmonary, cardiac, or liver involvement, although disease may recur in the transplanted organ.

Moderate or severe impairment of pulmonary function may predict mortality in patients with sarcoidosis who are infected with SARS‑CoV‑2. As in patients with other inflammatory lung diseases, during the COVID-19 pandemic, immunosuppressants should be used judiciously.